Everyone is comparing A Haunting in Venice to Hallowe’en Party lately, and with Halloween coming soon, I thought it would be fun to look at some of the party traditions Agatha Christie wrote into her book.

The end of October was already a pagan celebration, but similar to what happened with other observances, the “new” Christian religion usurped it. One or more of the Pope Greogories (Popes Gregory?) moved the day honoring martyrs from spring to autumn. Possibly, it was to replace Samhain, the Celtic festival of the dead, a logical church swap since All Hallows celebrated martyrs, saints, and other souls who had gone before. The night before All Hallows, or All Hallows Evening, was shortened to Hallowe’en and took on some of the Samhain traditions.

Incidentally, I have a terrible time remembering how to pronounce “Samhain,” except that I know it’s nothing like how it is written. I had to look it up again, so if you also have this difficulty, here’s your reminder: saa·wn. It’s Gaelic, another Celtic remnant.

One of the old Celtic traditions is that the veil between the world of the living and the world of the dead is at its thinnest on October 31. For some, that is a comforting thought. Think of the Mexican holiday Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead. Families bring flowers and food for loved ones who have passed on and share fond remembrances.

For others, spirits crossing over from the world of the dead is a frightening proposition. Hollowing out vegetables to use as lanterns to scare away evil spirits and dressing in disguise to hide from them are also old traditions.

Bobbing for apples, which is a major plot point in both Hallowe’en Party and A Haunting in Venice, is another custom, although it’s uncertain how it became part of Halloween. We know this is very old game because the Queen Mary Psalter, created in the early 1300s, illustrates apple bobbing, although the apples are hanging on strings rather than floating in water.

The term “pome fruit,” of which apples are one, is derived from the Roman goddess of fruit trees, Pomona. Bobbing for pomes was originally a mystical game for determining one’s true love. Pomona has nothing to do with the spirit world, but there are certainly plenty of apples in autumn. Perhaps the game became associated with Samhain because love leads to bearing fruit, as it were.

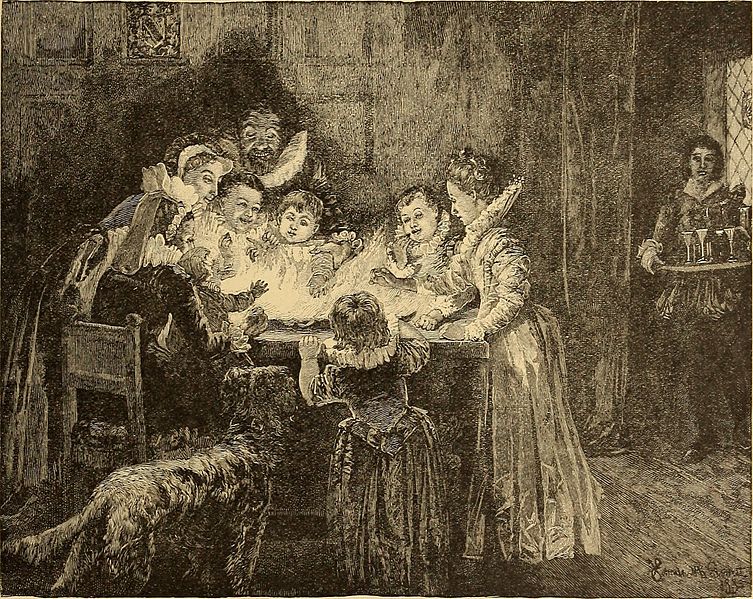

The guests in Hallowe’en Party also play snapdragon, another very old game. In the late 1600s, the poet John Dryden wrote “I swallow oaths as easy as snap-dragon/Mock-fire that never burns.” Of course, that’s not exactly true. In snapdragon, raisins on a platter are doused with high-proof alcohol and lit. Because it’s the alcohol on fire and not the raisins, a player can pick one up and pop it in their mouth with just a slight risk of getting burned.

As Miss Whittaker reminds us in the novel, snapdragon is “really more a Christmas festivity.” Lewis Carroll even describes his snap-dragon-fly as “made of plum pudding, its wings of holly-leaves, and its head is a raisin burning in brandy," which are all references to Christmas. Still, it must have made a spectacular show for the children.

Fire, such as burning raisins, vegetable lanterns, and bonfires, is used to light up the dark corners where evil spirits may lurk and England has long had an autumn bonfire tradition in Guy Fawkes Night, which is commemorated on November 5. Because the date is so close to October 31, Guy Fawkes celebrations have been increasingly overshadowed and some of its traditions, such as bonfires and fireworks, are being incorporated into Halloween.

Hallowe’en Party was published in 1969, so I don’t refer to it in Agatha Annotated: Investigating the Books of the 1920s, but there are a couple of references to Guy Fawkes in the early novels.

When Tommy escapes his captors in The Secret Adversary, he realizes “He had not shaved or washed for three days! What a guy he must look,” while in the short story, “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb,” Dr. Ames says to Poirot: “Surely you’ve not been guyed into believing all that fool talk?” Both uses refer to Fawkes.

In 1605, a group of Catholics planned to assassinate King James I by secreting explosives under the House of Lords. Fawkes was induced to join the group and given the task of guarding the explosives overnight and then lighting the fuse at the right time, but the mission failed when Fawkes was caught by the King’s men.

A public holiday was declared to celebrate King James’ escape from death. Celebrations included bonfires, on which anti-Catholics burned effigies of the Pope and Fawkes. In later years, when religious hostility was less fervent, only Fawkes’ effigy was burned, and young people had fun stuffing straw into old clothes and parading the scarecrow around before setting it on fire.

To be “guyed” means to be convinced, as Fawkes was, or to be ridiculed, in reference to Fawkes’ taking the rap for the failed mission. To look like a “guy” is to be ragged and unkempt, like the scarecrow effigy of Guy Fawkes. American scarecrow decorations in the fall may also be related to this English custom.

While the movie, A Haunting in Venice, may be more atmospheric than the novel, Hallowe’en Party, Agatha Christie was no stranger to spooky stuff. She wrote several supernaturally inspired tales that tingle the spine such as "The Last Séance" and "The Fourth Man." If you haven’t read them before, this might be your new Halloween tradition!

Photo Credits:

Guy Fawkes

Snapdragon

Queen Mary Psalter